While looking for things to do in New Orleans, we came across all kinds of tours. Walking history tours. Cocktail tours. True crime and cemetery tours.

One of them, however, tripped my bullshit detector: a ghost, voodoo, and vampire tour.

It wasn’t the ghosts and vampires that made my lips purse and my eyes narrow. It was the other part—voodoo.

Like many people, I knew very little about voodoo. What little I did know was based on movies and TV shows I’d watched as a kid. Think the Shadow Man in The Princess and the Frog and the cat ladies in Scooby-Doo on Zombie Island. (No, I haven’t and won’t watch American Horror Story, so I’ll stick with my animated examples, thank you very much.)

But I’d also heard voodoo is more than that. That real-life voodoo is nothing like the version Hollywood sells to us. That it’s a religion, a deeply misunderstood and misrepresented one.

Coming to New Orleans, I wanted to learn more—to see what voodoo really is. And my gut told me we wouldn’t learn much from a tour that lumped voodoo in with ghosts and vampires.

So Jason found us another tour. Led by a voodoo priest, free of charge except for the $5 service fee for reserving our spots online. We met with our tour group on Sunday morning outside Louis Armstrong Park, near New Orleans’ French Quarter. There, our tour guide, High Priest Robi, corralled us all by the gates to check us in.

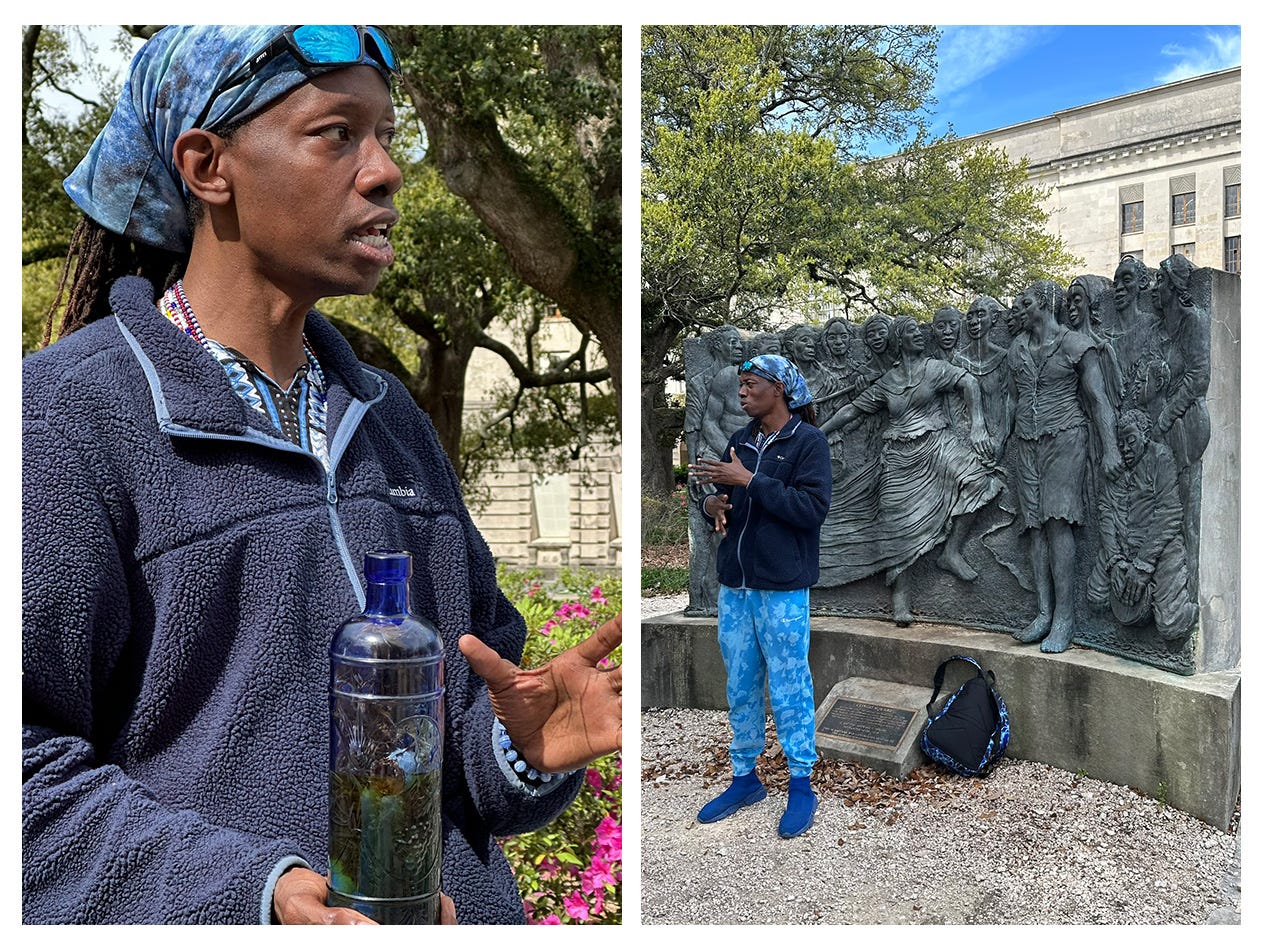

I didn’t know what to expect of a voodoo priest, but one thing about Priest Robi struck me immediately: He sang of modernity. He was in his late thirties, though he looked younger, and dressed in blue from head to toe, including his Columbia fleece and lightning-patterned backpack. The only non-blue items on him were a few strings of beads around his neck.

The most modern thing about him, though? His personality.

“They ain’t gonna make it,” he said after confirming that three people hadn’t arrived for the tour yet. “It’s Sunday mornin’. They hungover.”1

Priest Robi then kicked off the tour with a brief introduction, followed by a blunt message: None of us had to come on his tour. If we were staunchly racist, homophobic, ultra-conservative, or believed there was only one right religion in the world, we should stay at the gate. Because he was about to share evidence-based facts that would contradict those beliefs.

Jason and I glanced at each other. It sounded like we were in the right place.

I won’t go into detail about everything Priest Robi covered on the tour, namely because I can’t and shouldn’t.2 But in brief, he gave us a condensed history of voodoo, specifically Haitian voodoo, whose West African roots date back 6,000 years. He explained that there’s no single way to practice it; voodoo teachings vary from place to place and community to community. And he walked us around Louis Armstrong Park, which his family manages, and showed us the offerings they leave for the lwa (divine spirits) at various trees throughout the park.

As for today’s discrimination and misrepresentation of voodoo? It began with the French, who founded the city of New Orleans in 1718. They wanted to convert enslaved Africans to Catholicism, and to that end, they demonized the Africans’ religion and brutally punished them for practicing it. To survive, many Africans converted and taught future generations to do the same, because it would keep them safe.3

I really can’t do Priest Robi’s tour justice here, so if you’re ever in New Orleans, I highly recommend you check it out for yourself. In the meantime, here are a few things he shared that stuck with me.

Please note: I’m recounting these tidbits primarily from memory, so don’t go citing this post in your thesis. I apologize in advance for any inaccuracies that may be contained herein.

Voodoo and Catholicism have Similar Divine Hierarchies

In its most basic form, voodoo’s pretty similar to some mainstream religions. Voodoo recognizes one supreme god, Bondye, who created the universe and whose existence transcends human comprehension. Under Bondye there are the lwa—also called “orishas” in West African voodoo, or simply “spirits” in Louisiana voodoo—who have distinct purposes and personalities, and act as mediators between humanity and the divine. Before becoming lwa, however, they were humans who lived so virtuously that Bondye made them lwa upon their deaths.

“Sound familiar, Catholics?” Priest Robi asked us. Because Bondye sounds a whole lot like God, and the lwa sound a whole lot like saints.

Voodoo Dolls were a Record-Keeping System

Despite how many of them clutter the streets of New Orleans, voodoo dolls aren’t a major part of voodoo, and they’re certainly not used to inflict pain. Priest Robi’s description of how they were used in colonial Louisiana blew me away.

In colonial times, African slaves faced strict laws that dictated what they could and couldn’t do. Above all else, they were not allowed to read and write. So, when an individual went to see a hoodoo doctor—hoodoo is nature-based healing with roots in West Africa—they would work with the doctor to craft a doll that looked like them. The doctor would help the individual with whatever ailed them, e.g., a headache. Afterwards, the doctor would poke a needle into the doll; in our example, she’d poke it into the doll’s head. Then she’d set it aside, with other dolls resembling members of the community.

Later, when that same individual came to see the doctor again, the doctor would find their doll, see the needle—and remember that previously, this person had come to her with a headache. In this way, for the Africans of Louisiana, “voodoo dolls” served as a record-keeping system that didn’t involve reading or writing.

There’s Only One Authentic Voodoo Shop in New Orleans

And it’s Voodoo Authentica of New Orleans Cultural Center and Collection.

At the end of the tour, Priest Robi brought us to a circle of medallions in the park and asked us all to gather around him. From his backpack, he extracted a glass bottle—blue, of course—containing holy water. True to the spirit of his tour, he dispelled any mystery about it right away, explaining that it was made of rubbing alcohol and herbs. He offered to splash it on our hands.

We all took some. It smelled fantastic: a crisp concoction of mint, lemon, citronella, and herbs I couldn’t identify. I rubbed it on my hands, arms, and neck. (It was also a natural mosquito repellant, and I was going to get the most use out of it.)

Then we gathered around Priest Robi and closed our eyes while he prayed aloud. He prayed for our anxiety, depression, and worries to leave us. He prayed for us to find joy and happiness in the days ahead. Then he told us to breathe in deep and breathe out.

“Congratulations,” he said with a smile. “Y’all just participated in your first voodoo ritual.”

Two of the those people eventually arrived. The third was indeed hungover, as Priest Robi predicted.

Priest Robi gave us permission to take photos and record video of his tour, but I still don’t feel comfortable duplicating the information he shared here. I spent just 1.5 hours learning about voodoo, after all. I’m bound to get most of the details wrong.

I can’t say why Hollywood eventually jumped on that bandwagon, but hey, it’s not the first thing they’ve gotten wrong.

So interesting! I would love to go on a voodoo tour, and I would plan ahead and not be hungover, lol.